My kids, wife, and I spent a recent week in Philadelphia and New York City, seeing family, seeing friends, making new friends, walking on the High Line, going to a show, and doing gymnastics in Central Park. We did other things, too, and we had a great time. I was not the one who did the gymnastics.

What I can I say about New York City that hasn’t already been said?

Absolutely nothing. That’s what.

But what is new is a short story that was published just the other day at Bull magazine. Beware: it is, like other things I’ve published recently, highly sexual.

Why have I been writing so much about sex? The answer is that I haven’t. It was in 2020 and 2021 that I wrote a lot about sex, and I think it’s because thanks to COVID I wasn’t around other people anymore. Like, not at all. I was with my family, but everyone else was inaccessible, because I didn’t want to get sick or make others sick. For the longest time, like so many people did, I felt the absence of nearly everyone on planet Earth, and my isolation expressed itself in this unlikely, weird antieroticism. I wrote about sex and how awful it can be, even when everyone involved is at least having an okay time.

I was not the only one. I recall another writer on social media wondering publicly why everything she wrote at that time had turned abruptly sexual. She blamed the pandemic. I think she was on to something, and I don’t think it was just the two of us.

Anyway. It’s only now that my antierotic stories are getting published. That’s how it is when you’re a writer. You write something, and unless you want to publish it yourself you have to wait sometimes a long time for anyone to see it.

It’s not my fault. I don’t make the rules. I don’t even know how to make lasagna.

A Tale of Two Adaptations of the Novel The Hunter by Donald E. Westlake

I have not read The Hunter by Donald E. Westlake, but I’ve recently watched its two film adaptations. Or, rather, I watched the whole of one of them, and the first half of the other, which I saw before, once, a long time ago.

I watched these movies the way their creators intended: in increments of anywhere from thirty seconds to twenty minutes, over the course of seven to ten days, interrupted every time by the pressing need to go to bed so that obligations can be met the next day, or by a kid who wants to watch something else on the TV on which I have been viewing the film.

I’m not complaining. It’s okay that I don’t get to watch whole things in one sitting. It’s a privilege to be one member of a household, to have demands placed on me by a whole in which I am one part. It can be vexing, but in this season of my life it’s where happiness comes from.

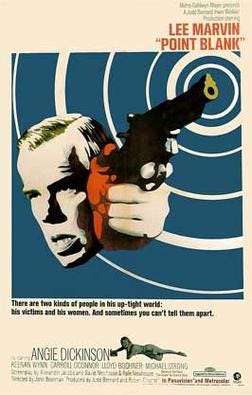

The first of the two adaptations I watched was Point Blank, directed by John Boorman and starring Lee Marvin.

As the poster for the film indicates, Lee Marvin plays a human head that has lost its body but grown a hand and bought a gun, so that it can talk to people and shoot bullets at them. Lee Marvin’s head is out for revenge, and for two hours it rolls around the city of Los Angeles, screaming about how great it was to have a body and how much he misses his arms and legs.

I’m just kidding, of course—haha!—but not about the revenge.

The story of the film is this: Walker, a criminal, is convinced by a friend and fellow criminal to participate in a low-stakes heist. But it turns out the stakes are higher than he was led to believe, and he gets double-crossed by his partner in crime and his own wife, who has fallen for the partner in crime. They shoot him and leave him for dead—but you’d better believe he’s not dead. He returns to the city, having convalesced, with all of his arms and legs, plus his torso and stuff, and gets to work.

Here is one of the weirder parts of the movie, in which Walker has returned from his supposed death and tracks down his wife, intending to murder the man who betrayed him, who he has reason to believe is living with her:

If you don’t feel like committing the minute or so to watching it, the scene at first consists of Lee Marvin walking through a cavernous hallway as his footsteps echo. The footsteps persist as we see his wife going about her day, and we see him driving around the city in search of her. The footsteps continue unnervingly through this montage until at last his wife enters her apartment and he bursts in behind her. He storms into the bedroom, where he empties his pistol into one side of the bed, which has no one in it. We can assume that it’s the side of the bed where he would be sleeping, were they still together. And so is he blasting away at the absence of his rival, or at the absence of himself? Whose blood is he really thirsting for?

I watched that scene and couldn’t believe it. It’s a bizarre series of images and sounds. It’s the kind of thing that makes me feel like it’s good to watch a movie from time to time.

It’s not long after that scene that the film becomes less hallucinatory, and more of a conventional thriller. But that scene does the essential work of throwing you off. It signals, in an unsubtle fashion, that things may not be as they seem, that all is not right with this guy you’re settling in to watch for a whole movie. He might be a vengeful ghost. He might be alive but dead inside, soulless and hollow. He might be dreaming all of this up as he lies dying where his wife and her lover left him full of lead.

It’s things like this that elevate the material, that make it more than an entertaining film about the angriest man in the world and his quest for revenge. Thanks to that notable scene, and subtler elements that appear throughout the film, Lee Marvin isn’t just a tough guy. He is a tough guy who is being constantly undermined by the film he appears in. He is depicted and taken apart at the same time. You might say he is deconstructed by the story in the course of its being told.

I don’t see any such thing in the other, more recent adaptation of the same novel that I spent some time with after watching Point Blank. That adaptation is the 1999 Brian Helgeland film Payback, starring Mel Gibson.

I remember having dinner with friends, years ago, at a conference in Los Angeles, and talking about Mel Gibson and what it’s like to see him in movies now that we know what kind of a guy he is when he’s not acting in films. Like, it’s true that if you watch Braveheart one evening you don’t have to first have a telephone conversation with Mel Gibson, and get to know the real Mel—and that’s a freaking relief, isn’t it?—but then, if you have heard that infamous recording of him shouting horrible things on the phone, it might change the way you see him in Braveheart. It might make you feel differently about that guy, and make it harder to buy into the many performances he has put on throughout his career.

I remember agreeing, at that LA dinner, that it does suck to watch movies with Mel Gibson in them now, like Braveheart. I also said I didn’t feel that way about some of his earlier films, namely Mad Max and Mad Max 2.

He wasn’t the driving force behind those films. He probably didn’t have much say in how they were made, as they were produced before his ultra-fame set in. They came before Lethal Weapon, which I gather was the turning point in his career, when he became a superstar.

He is, in fact, kind of an incidental part of Mad Max 2, in which he plays not a hero, really, but a guy who’s just trying to survive. As he barely scrapes by in life, he observes acts of heroism performed by others, and is coaxed into performing some himself, mostly reluctantly. But he’s a bystander, which is why at the end of Mad Max 2 and Beyond Thunderdome his enemies walk away and let him live. He’s just a raggedy man. He doesn’t matter at all.

So, I don’t know. When I watch Mad Max I don’t feel like I may have exposed myself to radioactive materials.

Payback is a different story.

Watching its first half, the other nights, was the first time since I heard Mel Gibson say the n-word on a telephone recording that I watched him in anything other than a Mad Max film. And it’s weird! It’s like watching Manhattan, in which Woody Allen has a teenage girlfriend, after it became public knowledge that that guy actually does have a thing for teenage girls and is confirmed to have acted on that attraction at least one time.

Watching certain scenes from Payback is really not that different from listening to Mel Gibson say horrible things on telephone lines. The production value is higher; you can’t deny that; but in both media, his attitude toward a woman is much the same.

In the footsteps scene from Point Blank, Lee Marvin manhandles the wife who betrayed him, grabbing her by the neck and then dropping her on the floor. That’s definitely not how you’re supposed to touch people, even if they’ve conspired to murder you. But in the analogous scene in Payback, Mel Gibson goes quite a lot farther than Lee Marvin did. He punches his character’s wife in the head. He presses her against a refrigerator, throws her to the floor, puts her in a headlock, and otherwise physically dominates her in a kitchen for at least half a minute, which in movie time is a very long time.

It’s really hard to watch this scene and not wonder how much more one of the actors enjoyed performing in it than the other actor in it did. I mean, come on:

While it’s true that I am given to hyperbole, and you can generally disregard most of the things I say—because nothing matters, and most mornings I wake up wanting to throw up all over the whole disappointing world—five minutes into this movie I decided it was the most fascist thing I’ve ever seen in my life.

What did I mean, when I said that to my cat in my basement? I don’t know. I say stuff like that sometimes.

But it’s really hard to watch Payback and—what? Take it seriously? I was never going to take it seriously. I saw the thing soon after it came out, on VHS, twenty-five years ago. I already knew it was nothing special.

But at some point in the last few years, I imagined a movie that doesn’t exist and never should, one in which two men race one another on a track in slow-motion. It’s clear from the beginning which of them is favored to win, and for the whole race the stronger, bigger man dominates his opponent, who lags behind from the beginning and never seems for a moment like he has the upper hand. The music in this hypothetical film is triumphant. The victory is pure. The strong guy wins, the weak guy loses, and everyone is overjoyed at the end because they love a winner and they hate a loser. There’s no suspense, and the only joy to be found is in seeing an outcome realized that you knew was coming all along. Anyone who doesn’t get it doesn’t know how to have a good time.

That’s not exactly what Payback is. But it’s not that different. The backstabbers have tried to kill Mel Gibson, but come on. He’s freaking Mel Gibson. You simply cannot keep a good Aryan down, so let’s watch as he beats up a woman, chokes a homeless man, uses a Jewish guy as a literal human shield, and shoots all of Lucy Liu’s Asian friends to death in a car. He has physical power and a pair of guns, and he’ll crush everyone who stands in his way.

Lucy Liu’s character, by the way, is a sex worker who doesn’t mind being punched and kicked and otherwise knocked around. She likes it! And you’d better believe she’ll hit you right back, which makes it all okay.

Am I missing the point? Maybe a little. Maybe a lot! The whole premise of this movie is that you are, as the poster advertising it says, rooting for the bad guy. Mel Gibson’s character is meant to be a horrible man. You’re not supposed to approve of what he does. Sometimes in life, in professional wrestling, and in TV shows and movies, the bad guy gets the audience behind him. It’s all pretend. What’s the big deal?

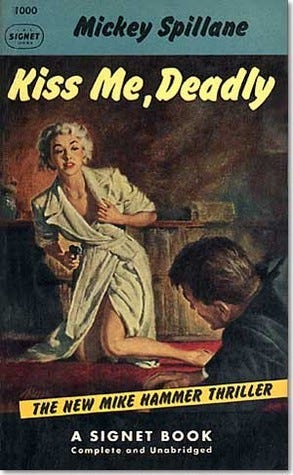

I don’t know that it is a big deal. What made me interested enough in these movies to spend part of this morning writing about them is the sheer disparity between them, the way in which one of them is made so as to take apart its brutish hero, to portray him but also dissect him, while the other seems to want to have the portrayal without any dissection or attempt at deconstruction. He’s just a terrifying man. He is unstoppable. He is Mike Hammer at the twilight of the twentieth century.

It seems to me that in most places where you go looking for tough guys, you find complications. They are undermined somehow, even if in the end they still triumph. Bruce Willis has a scene in Die Hard where he cries because he’s in physical and emotional pain. Arnold Schwarzenegger, in Predator, learns the hard way that being strong and having guns is not enough; he’s also got to be wily and smart. First Blood depicts its macho man as a traumatized war veteran who weeps in another guy’s arms. Early on in Aliens, you watch as nearly all of the tough-as-nails space marines are ripped apart and the survivors’ wills are broken.

Someone said online recently that the best action movies are those in which the hero gets roughed up at least a little. When you watch Indiana Jones get the shit kicked out of him, it makes you want to take his side that much more. It makes him a little more real. But then you’ve got action movie actors like Vin Diesel and Jason Statham, who have it written into their contracts that their characters can never lose a fight. They don’t want anyone to think they’re weak.

If there’s a lesson, I guess it’s that brutes are interesting when people who aren’t brutes decide how they’re portrayed. It’s why Dashiell Hammett is so much more interesting than Mickey Spillane. Et cetera.

Royalty

A check arrived in the mail yesterday. It’s a royalty check, for $36.42.

It appears that copies of Weird Pig have sold, and while it’s not much money, I’ll take it. I’ll take my kids out for ice cream sometime. I’ll buy $36.42 worth of drugs and smoke them all so that no one else can have them.

It’s the last check I’ll ever get from SEMO Press, publisher of Weird Pig. They are shutting down, but I have good news: I signed a contract last week with Black Lawrence Press, who have taken over distribution of Weird Pig.

Bad things happen, but sometimes other things happen that aren’t bad. Sometimes those other things are actually quite good.

But things have changed, now. I’ve gotten a royalty check.

There’s blood in the water, in other words. There’s money in my bank account, and I am a shark. I am going to seek out more of what I’ve tasted. I’m going to make more money from writing, if it’s the last thing I do. I will find a shipwreck, and the survivors who are flailing in the sea won’t see me coming when I tear their flesh apart and devour it, making myself rich.

Share this post