Our cat Oscar likes to go in the garage. He will do whatever it takes to get there. He bolts past us when we open the door, and when he does we tell him he is the worst guy in the world, that he is a villain. When we say that, we are correct.

There is nothing for him to do in the garage, no food for him to eat.

He stayed in the garage too long, one recent evening, and when someone finally let him back out he was starving. It had been at least two hours since his last meal.

He ate too much. He scarfed all the food he could and threw up on the floor.

That’s basically what this newsletter is, this installment of the Pig City News Weekly Register Hoedown Quarterly Review Times a Thousand. I want you to know, before we take this any further, that this is basically the writing equivalent of someone puking cat food everywhere.

I subbed for four days last week at the high school, the one where I like to be a substitute, because the kids there aren’t unruly—they are in fact quite ruly—and I can work there like I do at home. The students need nothing from me. They do their stuff and I do mine. I get paid to be at the high school, and I also earn money doing the work I would otherwise carry out in my unbelievably furnished basement.

I actually get more work done at the school than I do at home on some days. So, the way I see it, when I have a chance to go over there, and I don’t take it, I leave money on the table. About $150 per day.

Is that enough? No, it is not. But I have never been paid enough, and this is how it will always be.

A couple of years ago, I went to a menswear store, here in Kansas City, and admired the clothing. What blazers they had! What shirts. I looked at the price tags on some of the blazers and shirts and shook my head. I said to myself, “Maybe someday I will afford to put on something nice like this.” I was, at that time, forty-two years old. I realized I must have said the very same thing twenty years before then, when I was twenty-two, at a different clothing store. At the rate I’m going, it will take another eight decades for me to afford a nice blazer.

It’s a good thing I am so beautiful. I mean, thank goodness I look a hundred times better in my thrift store rags than the billionaires do in their finery.

I ain’t broke, but I am not a big earner. I am of little to no value to this world and its economy. I care too much about the placement of commas in sentences to see a comma in my weekly earnings figures.

But I have found, in this week of substitute teaching, that there is no sound that grates on me more than the sound of performative laughter. There was a lot of it at the high school on Monday. A group of kids huddled together and acted more excited than they could have been about stuff nobody really cares about. They described things they saw on TikTok, and as they did it they were beside themselves with put-on amusement. One of them would say something that was meant to be funny, and it wasn’t funny, but the person beside them would snort and hiss in a way that was meant to denote hilarity. It sounded something like laughter. It was not laughter.

I thought it was an evil sound. It sounded to me like derision, like the way bullies snicker back and forth to unnerve their victims. I thought it must be the way guards laugh in the off-hours at Guantanamo Bay.

After Monday, I didn’t hear much of that laughter anymore. I don’t know why not.

But we are living in evil times, and I am thinking of the people I have known who are dead to me, to whom I will never speak again. Or, if we do talk, it won’t be like it once was. They will not hear the noise it makes, but the next time we meet, the door to my heart will slam in their faces.

At a conference, some years ago, I was having a good conversation at a bar with a couple of other guys. We got along. We laughed at stuff together, in a way that wasn’t fake. It was, as the Irish say, “good craic.” We finished our drinks. I offered to fetch more of them, and I did. I bought my acquaintances their drinks. When I returned, I handed the drinks over, and in unison the pair of them turned their backs to me. They began talking to other people.

It was fine; they were under no obligation to continue entertaining my company. I walked across the room and spoke to a staff member from the university press that was putting the event on. She was nice. When my drink was empty, I left.

Maybe those two guys meant nothing by turning away from me abruptly. I doubt they planned to disregard me like that; it was just as likely an organic turning away from someone they were done talking to, who was wrong in thinking that getting us all more drinks implied that the conversation would continue. Maybe they are just like me, doing their best to be good people in a roomful of strangers and coming up short from time to time.

But if they were trying their best, they could hardly have done a worse job. Their disregard seemed altogether deliberate, and I trust my feelings.

It’s not a major loss to anyone—I didn’t know either of those people well—but I will never really speak to them again. If I encounter one or the other, I will ignore them or greet them without warmth. I will share no genuine laughter with them, and take no real interest in their lives. I know them now like I didn’t before, and I don’t like them anymore.

I am taking new medicine. I am having thoughts large and small. I switched from one antidepressant to another, and it’s like a switch has been turned on in my brain that was off for far too long. I have energy I haven’t had since 2019, when the wrong medicine started. I didn’t know it was the wrong medicine. It kept me from sinking too low, but I also felt sedated. I got used to it, so I didn’t even know that was how I felt.

Like most American men my age, I have listened to the Flash Gordon soundtrack at least 500 times. Every time I have put it on, I’ve heard Ming the Merciless ask his lieutenant, Klytus, “Are your men on the right pills?” I never considered that maybe, like Klytus’s men, I was not on the right pills.

Now that I am, I stay up late and think of the people from my life who have sort of arguably wronged me, at least as I perceived it at the time. I am rubbing my hands together and entertaining fantasies of retaliating against them by way of benign disregard, years after they probably accidentally slighted me, if you can even say for real that they did that. I don’t really think they did. I imagine it was just one of those things. I don’t care.

The old medicine made me forget that I have agency, that I can assert myself, that I can, when I’m greeted by someone I haven’t seen in a while, and I don’t like them now, say, “Hey, yeah, hi,” and look away, so as to communicate that they messed up somehow. And they are unlikely to give it another moment’s thought, but neither will I. We will continue on our parallel tracks and never truly intersect. It will be beautiful.

I went rock climbing with Incrediwife and our kids, at a place where rocks are climbed. Or that activity is simulated, anyway, as it’s indoors and there are no real rocks.

In the room with the highest walls, the ones that reach the high ceiling, I was too scared to climb all the way up. The others were not afraid. I learned that I am far more scared of heights than my wife and daughters are.

But the building had a big mirror in it, and I looked in the mirror and was reminded that I have shoulders. I have seen my own shoulders in other mirrors—this wasn’t any kind of special mirror—but this time I recognized them. I saw myself and knew who was there.

I’m not saying any of this is good. I am probably better off not seeing myself. I don’t doubt I should feel sedated, be tired all the time, and not initiate unilateral grudges with people I will never see again. I don’t care. I am deriving some joy from the grudges, and it’s an old joy, both in the sense that it’s an ancient kind of enmity, like what Neanderthals must have felt for one another from time to time, and also in the sense that it’s something I have found again, not knowing it was lost.

No one is going to pay. Nobody will suffer. I don’t want to hurt anyone. But I wouldn’t piss on the folks I have in mind if they were on fire.

I remembered, out of nowhere, a conversation I had with a wealthy man who was the head of a petroleum-related nonprofit in Washington, DC. He was my aunt’s boss. It was 1998, maybe, and he asked if I would ever be caught dead driving a Volkswagen Beetle. They had come back into style. I didn’t have a car at that time. I’d had to reach D.C. on a Greyhound, so I said that I would indeed be caught dead driving one. He seemed moderately disgusted by this, I think because he saw them as effeminate, or something, and I realize now that the way he felt about the VW Beetle was the way I feel now about a Cybertruck, more or less. Though for different reasons.

I read somewhere online that a guy is starting a publishing imprint that will prioritize men. They may publish women later, but for now it’s men whose books they will print and release to the reading public.

People online were up in arms about this, mocking the very idea that men’s voices and books have been neglected. I mean, haven’t these folks ever heard of Norman Mailer? Everyone was amused by the absurd development of a publisher that would only print books by men. The scorn poured down like silver.

And it is a dumb development, but I wonder how many men out there, even the ones who mocked the new imprint online, would admit in private that they don’t really have a problem with it, or can at least see where the push to start something like it comes from. I wonder how uncommon it really is, for male writers these days to feel like the world has passed them by.

I wouldn’t mind overhearing a conversation about this, by male writers who aren’t afraid of what consequences they might face for whatever they say. If a bunch of guy writers got together and spoke about it, without anyone knowing who they are, what would emerge? Would it be enlightening?

Probably not. But the other night, in this era of my new medicine, which has brought greater clarity into my life, I said to a man-writer friend of mine, offhand, that I feel like the world has indeed passed me by—“in, like, a hundred different ways,” I think I said to him.

I do feel that this is true, but I don’t think it’s because I am a man. And I am, as they say, such a man. Just look at my shoulders. I am like Kristof, from Frozen.

I feel that the world has passed me by, but it’s not the world’s fault. Not entirely. I had a career. I left it so I could raise the kids when they were little. Now they are old enough to not need me so much. I have taught them everything I know about revenge and vindictiveness.

The new publisher for men wouldn’t want me anyway. They’re in the UK, for one thing; and the guy who started it said he is looking for a hot new writer under the age of thirty-five to be their standard-bearer. I guess if you’re forty-four, or you’re thirty-six, and your work has been neglected because of the liability that is your gender, it doesn’t matter. You are too late and all dried up. You might as well light yourself on fire on the steps of the Library of Congress, to protest the way you and your ilk have been treated.

In my case, of course, it's not the staggering power of my fierce, Kristof-like manhood that’s keeping me from being a bigger name with more books published. It’s a combination of things.

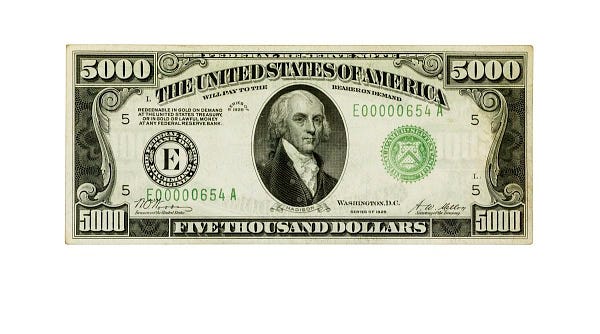

One of those things is my failure to write the sort of book that would be greeted with enthusiasm by literary agents and editors. The readers’ interests matter, of course, but it’s the agents and editors who decide what readers see on a large scale. They are the ones in control, and I haven’t written the right books for them. I haven’t met our literary culture halfway, or a third of the way, or wherever the literary culture meets writers. If I had done that, I would still be obscure and low-income. But who knows? Maybe I could be half a percent more notable, and have as much as 5,000 more dollars.

Another thing that accounts for my not having $5,000 and more prominently distributed books is that our culture is in a sorry state. Not only do most people never read anything, let alone books. Too many things—books especially—are boring and suck ass. I tend to downplay how good my writing is, because I’m not always taking the right medicine. But now I take the right medicine, and I can assure you, the things I write are good. But in a culture that’s so busy ass-sucking, what happens to things that are good? They occupy the margins.

There are, of course, other factors that aren’t things I made up so I would sound like a misunderstood vagabond, a maverick that no one understands.

Like, the world of mainstream publishing is small, it’s hardly a world at all, and nearly all of it is in New York City. I live more than a thousand miles from there. I am bad at social media in an age when follower counts matter, if no one knows you from something else.

I am not interesting, or hot enough to make up for not being interesting. I didn’t attend the best schools.

My heart races when people look at me too long. I enjoy sneaking through my neighborhood after midnight, and munching on whatever my neighbors are growing in their gardens. I find it almost impossible to resist the temptation of a fresh salt lick. I like to run in and out of traffic, and I run fast, but I have to do it on four legs, and I don’t have arms, so typing is difficult for me. My horns are always getting in the way when I want to do pilates. In other words, I am a stag. A lot of people don’t know that I am a stag.

And it’s not like I have stagnated as a writer. I’ve published three books! For that I am fortunate, and I know it, but I’m also aware of how much more there is out there. I didn’t make $5,000 from all three books I’ve published put together.

Why do I keep citing the figure of $5,000?

I know why it’s $5,000. It’s because that’s how much money the swine who control this country want to start giving mothers when they bring a new child into the world.

When I saw that thing in the news, I didn’t laugh. I didn’t even fake-laugh in that awful way they did at the high school on Monday. I just felt tired.

What would $5,000 do for a new mother? It would buy her some diapers, and formula if she needs it. She could buy a stroller, a car seat, and wipes. But she couldn’t buy the car she will need to ferry the child around, if she doesn’t already have one. She could buy fuel to put in a car, but she couldn’t pay for the insurance with that money for very long.

The $5,000 would run the hell out, and fast. It wouldn’t cover six months of daycare in a lot of places.

$50,000 dollars might make a difference. But even that much would not have been enough to offset my and Incrediwife’s hesitation to have a third kid, back when such a thing could have been done. It isn’t enough to make life much easier for the ones who have to do the countless hours of work it takes to raise kids. It would do nothing to calm a parent’s fear of what college will cost, if there are still colleges by the time their kid is old enough to attend one.

I don’t think anyone should have a kid for $5,000, and I suspect the Republicans’ floating that idea is nothing more than a way for them to try to cover their asses when they definitively end reproductive rights in the USA. They will outlaw all abortions once and for all.

They will restrict women’s access to birth control, so that only Jared Kushner’s wife can have some. If they put a little bit of money on the table, while they do that, then when they’re confronted they can say, What are you complaining about? Kids are great. Look at all this money we’ll give you if you have one. Come on, lady, give us a freaking break. Take this cold, hard cash from my sweaty Palpatine hands. And of course they will never actually give anyone that money.

It's really too bad that I’ve started taking the right medicine just before the Secretary of Health and Human Services halts its production and relocates me to a labor camp because I was defective enough to need to take pills in order to feel like other people.

One morning, while substitute teaching, I wrote 2,500 words of this newsletter—which I later revised, but still. Before that, on the same morning, I wrote probably a thousand words in my notebook. I applied for a remote full-time job, daring the world to continue passing me by. I supervised several dozen students who required nothing from me. I read a client’s short story.

It wasn’t like this a month ago, when I was on the old pills. A morning like this was pretty much out of the question.

It is incredible to me, how the substances churning in our bodies and brains govern everything we feel and do. It is so strange, that I can take a pill every morning that makes them churn this much better.

On the night of the third day of substitute teaching last week, I found myself getting emotional. It was in part because Incrediwife and I watched a truly gut-wrenching hour of television, an episode of The Pitt in which several bad things happened one after another. It hurt to watch them happen, because they did a good job making that show. My brother Jim wrote about The Pitt at greater length, and did a great job, and he lives in Pittsburgh.

But it wasn’t just the TV show that got to me. I always found, when I taught at colleges, that when a semester ended I felt like I stepped off the edge of a cliff. When the day came to say goodbye, I didn’t let on that I was having a hard time, and I was fine, really, it was nothing. But still I had been a part of something that now had to end. I had gotten to know people I would mostly never see again. I was a professional about it, and it was just another part of the job, but saying goodbye to the classroom and everyone in it was never easy.

I have learned this week that it doesn’t take a full semester for that cliff-edge feeling to manifest. I was only supervising those students not even a full week, and I didn’t even teach them anything. I was merely their stand-in teacher for four consecutive days. I barely spoke to them, because they were working, and I would rather give teenagers their space than bring my newly medicated energy into it.

But when you’re in a room with someone, ninety minutes at a time, several days in a row, a nonverbal assurance settles over the room. You develop an understanding, even if that’s nothing more than a silent agreement to not be jerks to each other. No one gets attached, but they become familiar, and that doesn’t make it hard to say goodbye, because you never even said hello. But still a separation takes place when somebody leaves. It doesn’t last, but you can feel it.

People can break your heart just by pretending to die on television. There are so many farewells we have to say, and at least it’s a mercy, I guess, that most of the time we don’t really have to say them.

Share this post