Incrediwife and I had the sort of conversation folks like us are having now. We discussed what new breakfasts we can eat, to replace the ones we usually have, which are made using several eggs. We are not egg fiends, but we consume them most mornings, often with kale or bell peppers scrambled in there. I love cuisine.

Now, thanks to the ghouls who are running our country, many of whom have never shopped at a supermarket, because they have always been so rich they have had others do everything for them, a dozen eggs in Kansas City cost $7.50. We have to moderate our egg consumption so we don’t lose too much money.

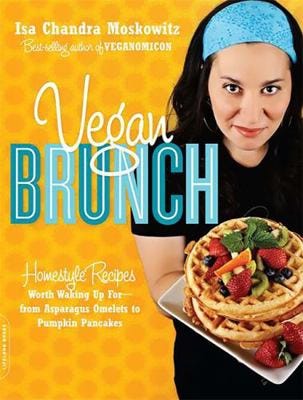

Ours, I realize, is not yet an extraordinary hardship. We have tofu in our refrigerator at all times. A tofu scramble is always an option. We like oatmeal. I have a vegan brunch cookbook. Incrediwife, our kids, and I are prepared for this moment.

I don’t know, though, what the next moment will be like. Will more people take the turn we have, and start making tofu scrambles instead of cooking eggs? If so, that could make tofu scarce. What will the next shortage be?

And what’s going to happen if thousands more retirees stop getting the Social Security checks that have kept them from going hungry and unhoused? That’s a much bigger problem than my household not having eggs.

I thought about getting a chicken coop and putting chickens in it. Chickens lay eggs. We could feed the chickens whatever we want, and take their eggs from them despite their protestations.

We don’t have much of a backyard, but we have no neighbors in back of our house. There are only the woods out there.

We could handle chickens. They make nice sounds.

I looked up chicken coops online, and my first thought, when I saw this one on Chewy.com, went something like, No way. I cannot imagine confining chickens to such a limited space for their entire lives, strictly so I can continue stuffing my face with their eggs. They would have no room to move around! They would not feel joy.

It’s without a doubt one of the most absurd thoughts I have had recently. Because, you know, chickens would be lucky to live in a small coop in my backyard. It would be about a hundred thousand times better than the places most of them live. You know?

So, yes, eggs cost too much, and I expect things to get a lot worse.

Things can always get worse. And they will.

But sometimes, when I enter a room, and one of our cats is there, I say hello to him.

You’re allowed to say hello without expecting a response. I don’t expect a response from the cats.

And starting a paragraph with a conjunction is a great way to abruptly change the subject in your newsletter.

But I am so tired of watching scenes in TV shows where one character tells another about their shared history. They retell a scene from their past, and the scene they retell is one they were both present for, which both of them remember.

It happens on A Thousand Blows. It happens on Yellowjackets, and probably every TV show. Even the good ones do this thing that drives me up the wall.

I wanted to provide an example of this in action, but when I tried googling it, not expecting much, or knowing how to describe what I’m going on about in a succinct google search, I found a website that’s meant to help people whose televisions have recently begun to address them specifically. Like, the programs aren’t for a broad audience of people anymore, the TV shows are instead directed at this one person. Their TVs are trying to tell them something important through the TV shows. It is apparently a symptom of mental illness, to become convinced that the TV is doing that.

I know why people on television tell each other about things from the past that both of them remember with clarity and don’t need to have explained to them. They are speaking to one another for the sake of the viewers. They are telling each other things they both already know so that whoever is listening will learn about them. It’s a way for the writers to demonstrate for whoever is watching who these characters are, where they came from, and how and how well they know one another.

It is a symptom of what some people like to call “character development.” And it is not only unnecessary, it’s a boring thing to sit through. It’s a way to check a certain kind of box, a way to help those who write in teams, the way TV writers do, feel like they are doing their jobs.

If you’re writing a story and it’s going well, you don’t have to go out of your way to develop characters. That’s what’s supposed to happen in the course of telling your story. We learn who the characters are through their actions and from how they speak. If you feel like you need to stop and have a character explain to the audience who they are, that’s a sign that of one of three things:

You are William Shakespeare, it’s the sixteenth or seventeenth century, and the rules are different because it’s the past and you’re writing for the stage.

You’re not doing a good job of telling the story.

You got some bad advice, at some point, and you feel as if you’re obligated to engage in this overt “development” of the characters you have created.

I was reading a client’s novel manuscript, the other day, and they did exactly the thing I’m complaining about. One character explained to another how they know each other, as if the second person would need the first one to provide him that information.

It made me think of Star Wars.

You all remember Star Wars, don’t you? The movie? I used to watch it all of the time, when I was young, and then George Lucas went back and added more special effects to it, which didn’t ruin it but did kind of sour it somehow. It made me less inclined to watch Star Wars again, on an evening when I’m feeling the warmth of the past and want it to get warmer. I know that the warmth will turn cold when I see all that CGI imagery go creeping across the screen.

But there’s that scene in Star Wars in which Obi-Wan Kenobi and Darth Vader face off on the Death Star. They fight using lightsabers, and while they do it they talk about their shared history. The way that conversation goes is a reminder of how unnecessary and counterproductive it is to have characters explain their histories to each other.

If a TV show writer from today were writing that scene, Obi-Wan would have to greet his old friend-and-apprentice-turned-rival by saying something like, “Darth Vader. It’s really you, isn’t it? You remember the last time we met, don’t you? We were on the lava planet. We stood on moving droids, and fought with our lightsabers on the droids. And I beat you, just as I am determined to beat you now.”

They have, of course, made more Star Wars since the fight that takes place on the lava planet. On the Obi-Wan TV show, they have yet another lightsaber fight after that one from Episode III. So that would be the scene he would talk about, unless in a future TV series the two of them have another lightsaber fight that comes after the one on Obi-Wan.

But the scene in Star Wars, which was made before everyone’s brain turned into mulch, doesn’t go that way. The viewer isn’t given an overview, in dialogue form, of these characters’ history with one another. Instead it goes the way it does when two real people who have a deep history meet again for the first time in a long time. They refer to the past in a way that suggests the nature of their shared history, without explaining it. “When I left you, I was but a learner,” says Darth Vader. What does he mean? We don’t know, but Obi-Wan sure does.

And it’s a great, memorable scene precisely because of all those things Darth Vader doesn’t say. The way they interact is interesting to watch because we know there are things we are left out of. It’s like overhearing your parents arguing with one another. You may not know exactly what’s going on, but you know enough to know that something is wrong. Your imagination fills in whatever blanks you’re left with. It runs wild.

Not so long ago, I watched The Hidden Fortress, the Akira Kurosawa film that inspired Star Wars. Lots of elements of Star Wars are present in it—actually, aspects of the whole original trilogy appear throughout it—and one of them is the battle between old rivals who finally face one another. They’re not meeting again, in this case—one of them mentions they never fought one-on-one before—but with even fewer words being exchanged between the pair of actors, the film conveys that they have a history. They duel with one another, and try to kill one another, but they laugh and smile when they meet. It tells you the situation is complicated, and that these men are complicated, or at least that they enjoy putting their lives on the line and having a good, potentially fatal contest like this one.

That scene from The Hidden Fortress is slow, but it’s tense. It makes you want to watch it, because the people who made it put a lot of work into making it good.

The thing, of course, with TV shows where characters tell each other stuff they already know is that the shows are made with the expectation that no one will really watch them, not even the people who are sitting in their living rooms or bedrooms with the shows playing on their TVs. We’re all looking down at our phones, not up at our TV screens, so important scenes often begin with loud noises. They tell us to look up and pay attention.

That kind of sucks, I think. But I don’t think it’s the fault of the viewer that they’re so inclined to look at a phone and not at the TV. I suspect that it’s due to the shows not being very good, and not the other way around.

One of the problems with having characters tell each other stories from their lives that they already know about is that it’s boring. I don’t want to watch people reminisce. I want to see them get angry and make bad choices. I want to feel a little bit left out, so I have to pay attention in order to find out what’s going on.

I was reading the Foreword that Rumaan Alam wrote for the latest edition of the Helen Garner novel The Children’s Bach, where he writes of when he first read it, "I remember the sense that I was not quite understanding something, which I consider the most exhilarating feeling a work of art can elicit.” I recognize in those words the thing I’m trying to explain here, the thing that gets lost when our storytellers are too careful to ensure that the reader, listener, or viewer, can keep up with them. I don’t want them to lose us, of course, but there should be some risk of that happening in the course of the story unfolding. There should be stuff in there that isn’t told to us explicitly but which we can see and hear if we really watch and listen.

The prestige TV show that does this best of all, and my personal nominee for Greatest All-Time Television Experience, is The English, a show that can be at times completely baffling, as it withholds fairly crucial information from the viewer until about the series’s midpoint. There is a villain in it, and he gets talked about starting with the earliest scenes. But this bad guy doesn’t actually appear for several episodes, so you’re left to wonder who this guy is that Emily Blunt is talking about with everyone she meets. Why does he matter? What has he done that makes him so bad? We have no idea. But the way things are written and performed makes us curious, so we pay attention.

How much does any of this matter, in a world where hardworking Americans have to start making tofu scrambles for breakfast instead of scrambled eggs because there aren’t many eggs anymore because the government is run by some of the worst people of all time?

It matters a lot. And not just to me.

I haven’t been teaching as a substitute much lately, because there’s hardly been any school. The district has had twelve snow days since the year began.

But I went in for an afternoon shift the other day, at the high school, and the students in an English class were planning their own dystopian works of fiction. Or, they weren’t really planning the stories they were going to tell, they were planning the dystopias. They were tasked with deciding how the totalitarian governments came to power. They were to design some propaganda the regime used to keep its populace in line.

It seemed like a fun project. I would have liked doing it in high school. But as the students worked they talked about the plots their stories would have. One of them boasted that they were very good at spotting plot holes in the movies they watched and the books they read.

I kept my mouth shut, because I have found that students don’t want me to speak to them. When I do, they look away and wait for me to stop talking, then eventually they resume their conversations.

But I wanted to scream! I wanted to implore them to erase the word “plot” from their vocabularies. It is a misleading word, one that tells you to focus on one thing when you really ought to care about many other things.

The problem with “plot” is that people think it’s the most important thing. They are convinced that a story’s plot must be watertight if it is to pass muster. If there are holes in a plot, then the narrative fails for these folks—when it really doesn’t matter if plots have holes in them. What matters is whether the reader or viewer is lulled into a state of not caring about such things. Stories are not made of plots, they’re made of words, and it’s the words that matter, or the images and sounds, in the case of a movie or television series.

I want everyone who composes a fictional narrative to lend no thought whatsoever to its plot until the first draft of it is finished, at the earliest. Make the thing interesting. Make the words go in a way that makes people want to keep reading it. Fuss over the structure only once you have done that extremely hard thing.

Am I right about this? I don’t know.

But I do know I enjoyed my brother Jim’s recent post about developments in American politics, which features a photo of our mother at a recent protest against what’s been happening in American politics.

That’s right: my mom goes to protests now.

We have some ancestors in our lineage, Aunt Anne and Aunt Lil. They were sisters who traveled the world and climbed mountains together. They never married. They were suffragettes, and as I understand it they marched. They protested. I never met them—they died well before I was born—but since I first heard about them a certain pride has pumped through my veins, along with my blood and all the other stuff. Their actions have resonated down the generations, and now my mother is renewing that spirit in our family. She is setting an example for the people in her community, for me, for my children, for my nephews, for everyone. There’s a lot of bad news that’s bringing everyone down, and rightly so, but my mother is not backing down.